Yesterday in class, we talked a lot about how historians think about and demonstrate causal influence. I took some photos of notes that we assembled on the chalkboard.

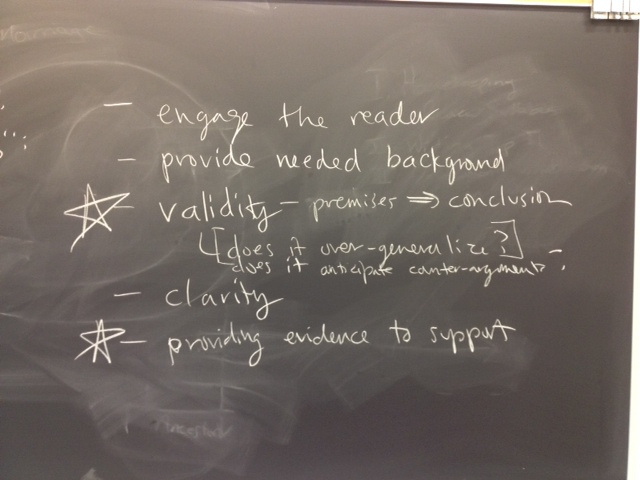

First, we discussed what makes an article persuasive. Persuasiveness includes things like the clarity and rhetorical style of the article, but we also discussed why the soundness of the argument and the use of evidence are the most important criteria for historians in deciding whether an article makes a good case. These two areas will be the most heavily weighted assessments on your final research paper.

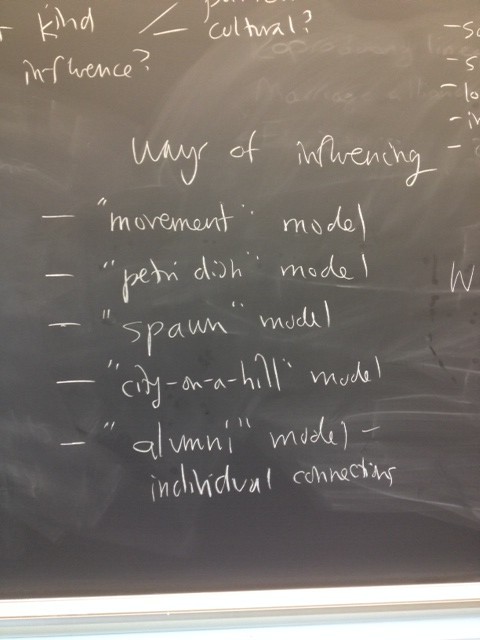

We then put on our “lumper” hats and talked about various ways that utopian communities might influence the culture outside their boundaries:

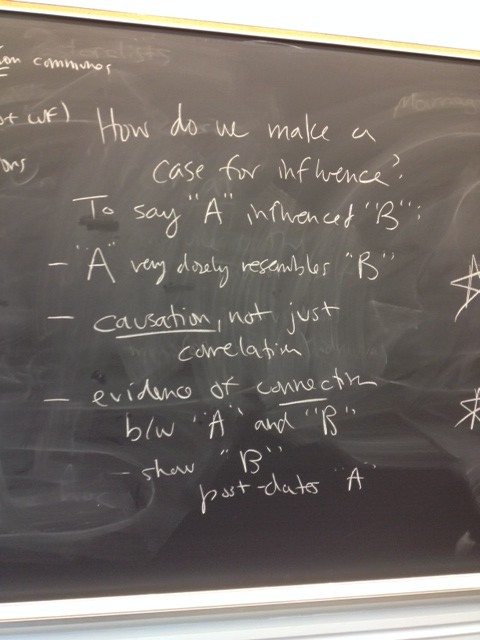

Of course, all of these are hypothetical ways that a community “A” might influence “B.” To actually demonstrate such influence, a historian has to show a number of things using specific evidence. We can’t assume a priori that influence did or did not occur in a certain way, and we can’t assume that “B” was influenced by “A” just because it came after the fact. (That would be a post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy.) Demonstrating influence isn’t a simple matter, and it involves at least the following steps:

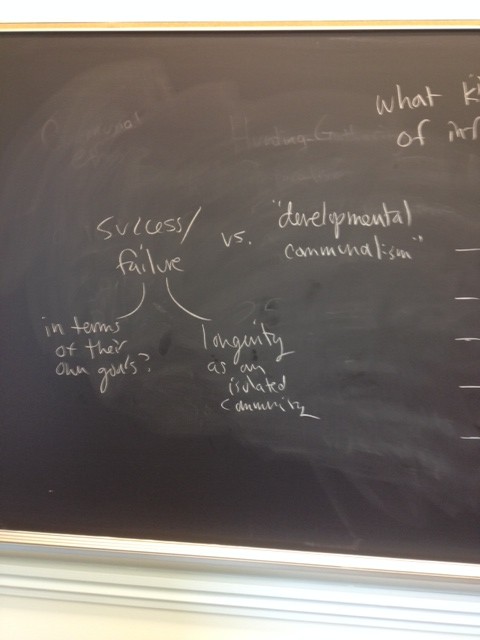

Finally, we briefly discussed how different scholars of communes think about what happens when a commune dissolves. Some think of the end of a commune’s life in terms of success or failure and try to figure out why the community failed. Others, like Pitzer, believe the dissolution of the community might be evidence of its success.

These points may be worth revisiting later in the semester, especially if you want to make an argument about influence in your paper.